How to Create a Compelling Character in Minutes

If you’ve got an idea for a story, but are stuck on how to bring your characters to life, then there’s an easy formula to give you a head start. To create a compelling character, you need three simple things: goal, motivation, and conflict. These three things make the basis of any interesting character, and in no time, they’ll be ready for you to bring them to life on the page.

The formula to create a compelling character

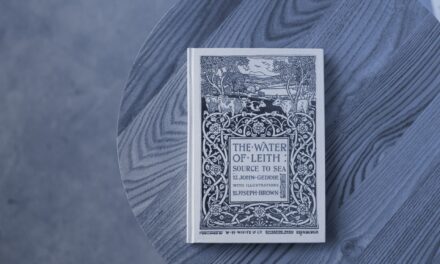

While every character and plot in the history of literature contains goals, motivations, and conflicts (it’s the backbone of storytelling, after all), it was writer Debra Dixon who first honed in on it. In her book, GMC: Goal, Motivation and Conflict: The Building Blocks of Good Fiction, she was the first to put the process into uncomplicated terms and make it accessible to authors who might never have considered its simplicity before.

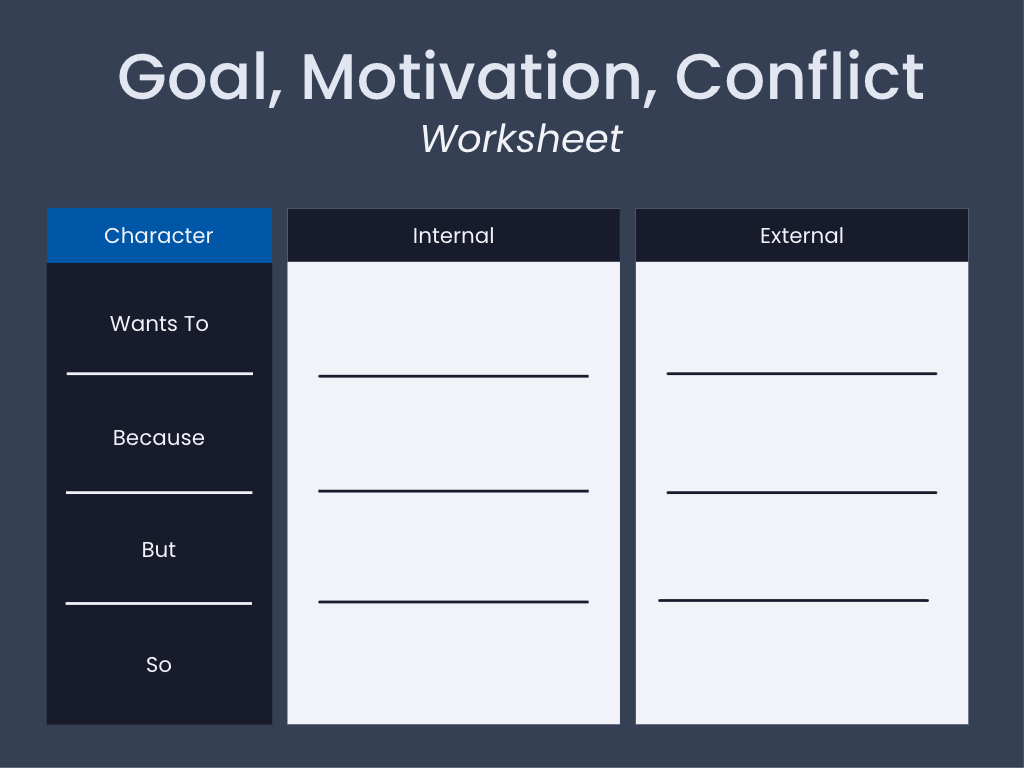

The formula is straightforward:

[Character name] wants [goal] because [motivation]. But [conflict] so [action taken to overcome conflict and achieve goal].

It asks the following questions:

- What does your character want? (Goal)

- Why do they want it? (Motivation)

- What’s stopping them from getting it? (Conflict)

- How can they overcome it?

Let’s take the 1939 film, The Wizard of Oz, as an example:

[Dorothy] wants [to return home to her aunt and uncle] because [she has been stranded in a faraway land by a tornado]. But [a witch seeks revenge for the death of her sister and the theft of her ruby slippers] so [Dorothy must go on a dangerous journey on the yellow brick road to ask the Great and Powerful Oz for help].

Applying this same method to the character of the witch, we would have:

[The Wicked Witch of the West] wants [revenge on Dorothy Gale] because [she accidentally killed her sister and stole her ruby slippers]. But [Dorothy and her friends defend themselves against her attacks] so [the witch must face Dorothy herself or die trying].

It’s such a simple exercise and gives you a compelling character in a matter of minutes. That’s not to say you won’t have to do more work to give your character a personality and really flesh them out, but it’s the fastest way to set out a framework without wasting hours on the minutiae of appearance and backstories. That can come later.

You should use this formula for your characters’ internal (emotional) and external (physical) motivations. And if you’re stuck on a particular scene, you can repeat the exercise on a micro level to see how your characters might behave in their current circumstances. It can even help with a birdseye view of where you might have plot holes or pacing issues.

Outline the goals, motivations, and conflicts for each of your characters, no matter how minor. This will allow you not only to create a compelling character, but write scenes full of tension – you’ll know exactly how each character’s goals and motivations might conflict with those of another.

External vs. Internal

Every character in your novel or story will have both internal and external elements that drive them. Their internal and external drivers will often be at odds with each other.

When defining external goals, motivations, and conflicts, you’ll be looking at their physical and visible experiences. This is essentially how the story will play out.

In contrast, a character’s internal goals, motivations, and conflicts are hidden from the outside world. They’re about what your character thinks, feels, and desires. It’s what they want, and what they need to overcome, to be the person they want to be.

Goals: What does your character want?

By being specific about what your character wants, you will have a clear idea of how your story will end. Their external goal is about what they want to accomplish or achieve. An external goal should be clearly defined – something you can tick off as done or not done.

When your readers reach the last page, they should know whether your character has reached the goal. Think of the Dorothy example from earlier. Her external goal is to get home to Uncle Henry and Aunty Em. By the time we reach the end of the film, it is clear that she has achieved that.

On the other hand, internal goals do not need the same binary state at the end of the novel as a character’s external goals. Because they are emotional, there is more scope for subjective interpretation. In fact, by the end of the story, your character doesn’t need to have achieved their internal goal at all. It might be outside of their control, they might have grown to rethink it, or they may have overcome a personal conflict that makes the goal irrelevant to their future.

Motivation: The “why” behind the want

A character’s external motivation is the “why” directly connected to their external goal. It’s the reason they have for moving the plot forward. It’s the one question that is most important to almost every element of plotting. Get this answer right for your character, and the rest will follow.

With any event in your plot and any character motivation within it, always stop to ask “why.” If you can’t immediately answer that question, then you’ve got a plot hole. Knowing motivation means your characters have intention, and you’ll be able to move your story forward.

In contrast, the internal motivations of your characters are the “why” behind their feelings. With an ephemeral and emotional goal, you need to ask why they feel that way. If your character wants to feel like they belong, for instance, their internal motivation will be determined by why that might be. Were they bullied as a child? Did they come from a family of outcasts? Why is fitting in so important to them? The answer to that question will allow you to write a compelling character with real emotional depth.

Conflict: What is getting in the way?

The events, villains, and other tangible forces create the external conflict of your story. An antagonist is often the most obvious source of conflict in any narrative, but the circumstances of your protagonist, or the actions of the characters that surround them can also play a part in creating conflict.

Whether the external conflict comes from a person, social or environmental factors, or is politically motivated, it will be the central driver of your plot and how your character fits within it. The protagonist and antagonist of your story will likely serve as the arbiters of conflict for each other, creating the dramatic tension and the ultimate climax of your story.

Once again, internal conflicts can be much harder to define. You’ll need to think about what gets in the way of your character reaching their ideal emotional state. Using the previous example of a character who just wants to belong, that character might be forced into a leadership position that requires them to be an outsider. This could be a conflict that they overcome by accepting their role as someone who simply won’t fit in, or they might give up their special position to seek a life of quiet and reflection within a small community and ultimately attain their emotional goal.

To add extra tension to your story, you can build your conflict around the opposing goals of two characters. If the goals are at odds, they will share a conflict, giving you a built-in climax for your narrative.

A lot of time and effort goes into crafting a great story, but by sparing a few minutes to bottom out the goals, motivations, and conflicts of your characters before you start delving into them too deeply, you will cut out a lot of the hard work of trying to shoehorn it in later. It’s like placing the corner and edge pieces of a puzzle in advance – it doesn’t take long, and you can see how the pattern needs to develop, cutting down on a lot of trial and error.