Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules for Writing: How Useful Are They?

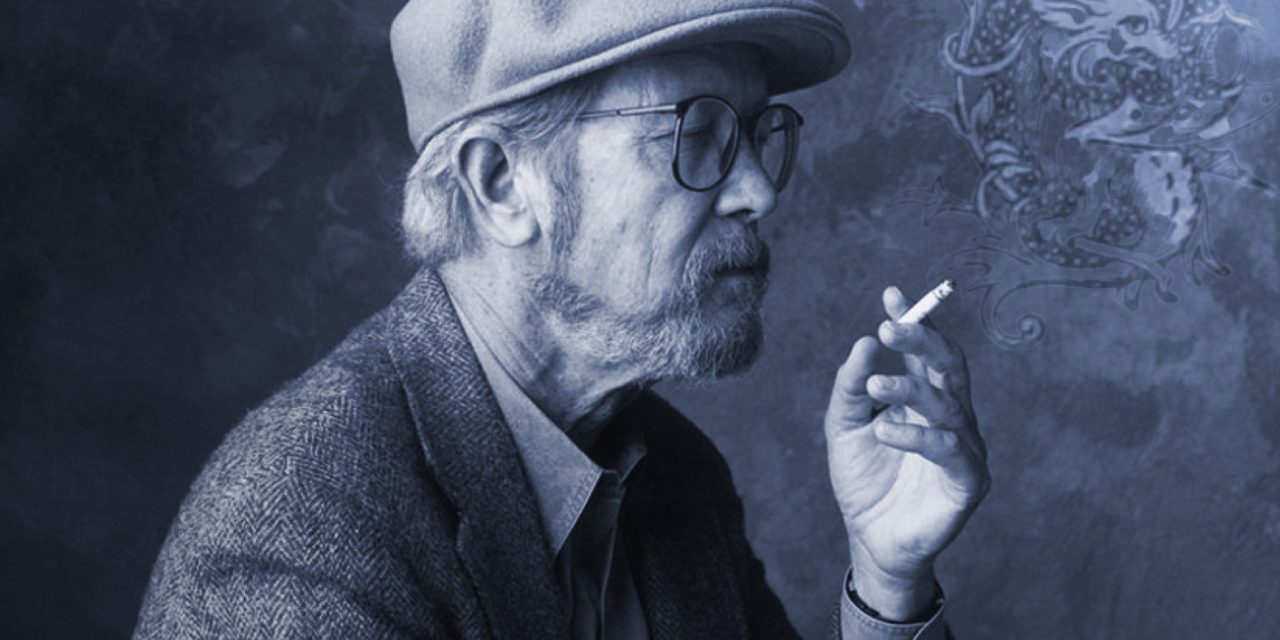

On my 25th birthday, my sister gifted me a copy of Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules for Writing. Like most writers, I was constantly looking for that spark of inspiration; that one piece of text that would make it all click into the place so I could really say I knew how to write.

But like all pieces of writing advice, there is simply no one-size-fits-all approach. What works for one writer may not work for others. But where writing advice does come in useful is giving you hints on things to try. It gives you the framework to practice and discover for yourself what works, and what doesn’t.

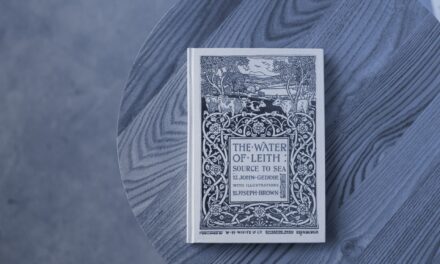

Elmore Leonard’s 10 rules for writing have outlived the titular book from which they come. The little illustrated hardback I still have at home is now quite a rare find. But the rules themselves are still shared prolifically all over the internet, digitally reprinted again and again.

But how strictly should we adhere to Leonard’s “rules”? Or can we view them more like guidelines? With constant redistribution, the rules have lost their context and, instead, are shared as one-liners. Some of the advice is actually a lot more nuanced, so let’s take a look at why that advice exists and how we can take it within a context that works with our own stories.

1. Never open a book with weather

Despite the clarity and directness of the rule itself, there are actually a lot of caveats included within this. Starting with a description of the weather has become a cliché, so the rule definitely makes sense from that context.

However, Leonard advises against starting a story with a description of the weather, unless it directly relates to a character’s reaction or serves a specific purpose, which for me is the important nuance that lots of people miss when they share this advice. He argues that readers are more interested in the characters and their actions than the atmospheric conditions, which is true, but he also acknowledges that there are moments when it can serve your story if you know what you’re doing.

If you fall back on the weather because it’s easy, and you can’t think of anything else, then the rule stands. If you’re making a conscious decision that serves your story, feel free to ignore it.

2. Avoid prologues

This is a contentious rule, and actually has a pretty even split amongst writers and readers alike. Leonard suggests steering clear of prologues in fiction because backstory can be woven into the main narrative without the need for a separate prologue.

I definitely agree with this. Both as a writer and as a reader. I’ve rarely read a prologue that enhanced the story for me. By the time the information revealed in the prologue becomes relevant, I’ve usually forgotten it because it was given without context. And if I haven’t, it means that I got an info dump early on without decent world building along the way.

That said, this rule is firmly a preference, and I don’t think should be taken as a hard and fast rule. Some readers enjoy prologues and find their reading experiences enhanced by them. The trick here is to know your audience. If they like prologues, then prologue away. If they don’t, or there’s a better way to share the information than in that form, then don’t.

3. Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue

According to Leonard, using verbs other than “said” to attribute dialogue can be distracting and take the reader out of the story. He advises writers to let the dialogue itself convey the tone and emotion of the characters.

Personally, I think this is bad advice as it’s far too easily misunderstood. The key piece of advice here is to let the dialogue itself convey the tone and emotion, but that’s not how most people will understand it. When looking at the rule itself, without context, it will lead to some very boring dialogue.

While it’s true that overusing dialogue tags like “exclaimed,” “shouted,” or “whispered” can be distracting, the occasional use of a more descriptive verb can add depth and variety to your writing. Like any part of writing, it’s all about balance and diversity.

What Leonard is trying to do with this advice is encourage writers to craft strong, expressive dialogue that stands on its own. However, there may be instances when using a different verb can add clarity or emphasis to a specific action or emotion. The key is to strike a balance and use them sparingly.

If your dialogue is well-crafted, the reader should be able to infer the tone and emotion without the need for excessive dialogue tags. However, completely avoiding them can lead to flat, monotonous exchanges.

4. Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said”

Poor adverbs. Everyone seems to hate them.

I get why adverbs are so universally maligned because they do lead writers to lazy writing decisions. But they exist in the English language for a reason, so denying them so completely always seems a bit excessive to me.

Leonard advises against using adverbs to modify the verb “said” because he believes it is a sign of weak writing. He argues that well-written dialogue should convey the intended meaning without the need for adverbs. In this, he’s right.

The main arguments against them boil down to:

- Often, a stronger/more expressive word works better than a weaker word modified by an adverb.

- Adverbs are often redundant and can be dropped without information loss (think “smiled happily”).

- New writers abuse adverbs to make their prose prettier, leading to bloated writing filled with unnecessary information.

- Overuse can slow down your writing as they often make sentences longer.

Once again, this is a rule you can break if you know how to do it well. When used in context, adverbs can make your writing clearer and more precise, emphasise a specific detail with a single word that you want to highlight, contribute to sentence diversity, or replace an unnecessarily descriptive phrase with a single word for clarity.

Ultimately this rule comes down to experience. If you know how to use an adverb well, then adverb away. If you’re not sure, then avoid them.

5. Keep your exclamation points under control

This rule, I absolutely agree with, and I am so, so guilty of doing this myself. Exclamation points are designed to emphasise, so if you use them too often, that emphasis gets completely lost, like the boy who cried wolf.

Leonard’s advice is to limit exclamation points to two or three per 100,000 words of prose. I think this is probably a bit excessive, given that a lot of published works don’t even reach that word count. But the point still stands. Use them sparingly.

This rule encourages writers to convey excitement, surprise, or emphasis through strong word choice and sentence structure rather than relying on punctuation. I think this is generally good advice. However, there may be instances where an exclamation point is appropriate and effective, especially in dialogue. So use your best judgment.

6. Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose”

This rule is essential about avoiding clichés. Honestly, of all the rules, I think this one stands on its own.

This rule encourages writers to find more creative and original ways to convey sudden actions or chaotic events. By avoiding clichés, you can create a more immersive and engaging experience for your readers.

It’s important to note that a cliché is not the same as a trope. Use tropes to your heart’s content. This is specifically about language choices that lose meaning because of how often they are used. The notable exceptions to this rule would, of course, be dialogue if your character often uses clichés or if you’re satirising them.

7. Use regional dialect and patois sparingly

Unique character voices are one thing, but as a reader, it can be incredibly difficult to immerse yourself in a book if you’re constantly having to analyse how a character speaks in order to understand it.

Leonard acknowledges the importance of capturing the unique voices of characters, but he cautions against overusing phonetic spellings and apostrophes to represent regional dialects or patois.

Great writers can infer dialect and voice without overusing phonetics. It’s all about writing good characterisation and great dialogue. You can capture the essence of a character’s speech through word choice, rhythm, and including the odd colloquialism just as easily as you can through phonetic spelling and apostrophes.

Character speech is often determined by context, and it’s far too easy to fall into stereotypes if you’re relying too heavily on phonetics. It can also be a huge distraction. It’s enough to know that someone is speaking with a French accent without ‘aving to show ze speech exactly (see how awful that is to read? I’d like to apologise to all the French. I felt dirty just writing it).

8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters

Leonard can prise my character descriptions from my cold dead hands.

While he does have a point about over-describing, I’d argue this applies to literally any part of writing. I love a well-placed, well-written character description. I like to be able to imagine the characters I’m reading about.

Leonard advises against providing extensive physical descriptions of characters, citing Ernest Hemingway’s minimalist approach as an example.

In Ernest Hemingway’s Hills Like White Elephants, what does the “American and the girl with him” look like?

“She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story.

Sorry Leonard, but I need more than that!

Honestly, I think this one comes down to personal taste. The rule is meant to encourage writers to reveal characters through their actions, dialogue, and interactions rather than relying on lengthy descriptions, but sometimes, you just need a description.

Like any writing advice, I feel like this one falls back on the tried and true “everything in moderation.” Some description, good. Over describing, bad.

9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things

Let’s be honest; this is the same rule as above and also one that I wholeheartedly disagree with. I also think that this advice is incredibly genre-specific. Elmore Leonard wrote crime fiction, thrillers, and westerns, all of which tend to be action and plot-heavy so do well with pared-down descriptions.

In genre fiction like horror, fantasy, or sci-fi, description is essential for providing a sense of time and place. Like any description, it is possible to go overboard, but I think certain genres lend themselves very well to detailed descriptions.

While he does suggest avoiding overly detailed descriptions of settings and objects unless it is essential to the story, this “rule” once again minimises that nuance into a one-liner, which I think does writing communities a disservice when disseminated in this way.

Vivid descriptions can enhance the mood, atmosphere, or themes of your story. Use your best judgement when writing descriptions, and do whatever best serves your story.

10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip

I agree with this, but not necessarily in the writing part of producing a book. For me, this is an editing job.

Getting too bogged down in relevance, especially during a first draft, can completely take you out of the flow. I’m a big fan, of writing everything that comes into your head in your first draft, and then going through it later to find out what’s relevant and what’s not. It’s hard to know what readers will skip unless you’ve been a reader of the work yourself.

Leonard’s advice is meant to encourage writers to be mindful of the parts of a story that readers might be tempted to skip, like lengthy passages of prose, monologues, excessively long descriptions, or unnecessary details. It’s designed to push writers to be concise and purposeful in their writing, ensuring that every word and sentence serves the story and keeps the reader engaged.

He’s absolutely right in that, but for me, this is never something you should worry about in a first draft. Terry Pratchett is often quoted as having said, “The first draft is just you telling yourself the story,” and I think this perfectly applies here.

Don’t be afraid to explore your world, over-describe, and insert unnecessary details in your first draft. No one ever publishes their first draft, so it’s the perfect time to explore your world and your story. Instead of following the rule to “leave out the part that readers tend to skip,” instead, aim to take it out in editing.

The most important rule: If it sounds like writing, rewrite it

Leonard ends Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules for Writing with a single rule that sums up all the others: If it sounds like writing, rewrite it.

This is pretty sound advice for when you’re editing. You want your prose to be immersive. If it reads like writing, it won’t be. But to determine that, you need to approach your work like a reader.

We should all strive for a natural, authentic voice that resonates with readers and avoid excessively elaborate or artificial language. The aim should always be to create stories that feel genuine and relatable.