Why do writers love to torture their characters?

“Why do writers love to torture their own characters so much?“

One word: conflict.

Conflict is the chef’s kiss in a story. The secret sauce to writing from plot to scene level. And the real reason a reader will enjoy your story and character.

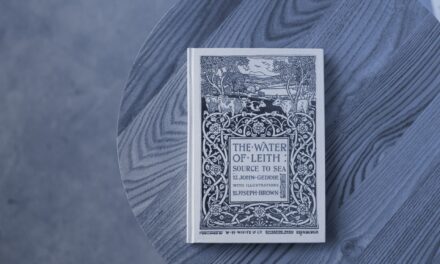

I love pretty prose and world-building, but both will only get you so far. Because writing is so much more than just writing. It includes the art of storytelling. And that requires conflict. For without conflict, your story lacks content; regardless of your story length, genre, writing style, and subject.

What is conflict?

In its simplest form, conflict is when a character confronts an obstacle that hinders them from reaching their goal.

This obstacle can be as large as Thanos wanting to erase half the population in the universe, to something as small as a farmer out fishing and realizing he’s out of bait. It also ranges in use. Conflict can become a major plot point in a story–such as the main antagonist causing your hero to hit an all-time low–or it can also be a quick beat in a scene with two characters having an argument.

There are two types of conflict in a story: external and internal. External conflict is what happens between your character and their outside world (think main external plot), while internal conflict is what happens between your character and themself (their inner struggle, or character arc).

Conflict is everywhere in storytelling, and on paper, it’s a simple concept to understand. And yet, sometimes, it feels like it requires total mastery to write it.

Conflict must be meaningful to your story and character(s). The obstacles must help move your story forward, move your character to determine a new plan to reach their goal–and create growth and change for the character, too.

Conflict is not just adding random fight scenes in an action story, or throwing in a love triangle for the fun of it. There has to be a clear, meaningful “why” behind that obstacle, external or internal, existing. This means a clear explanation of why you’re throwing it in the story, why your character has to face it, why it affects your character’s goal, and why it affects the plot and moves it closer to the end of the story.

Why we like conflict

Let’s experiment with a question. Do you enjoy a story, whether in a video game, movie, or novel, because of its ending? Do you enjoy a story simply because a hero succeeds?

Or do you enjoy the story because of the journey to the end? Because of how the hero succeeds? Because of the reward after the struggle? And because of how the hero transforms throughout the story?

Your intuitive response should have agreed with the latter.

As they say, it’s all about the journey, not the destination. This is why we, as consumers of entertainment, love conflict; and, therefore, why we, as writers, love to torture our characters.

We all want to see characters struggle to reach their goal. We want to see what that struggle does to the characters and how it changes them. We don’t want a story that gives a character a straightforward journey to succeed. That’s boring.

When we read the news, we are more enticed by headlines like “Man turns his life around with charity after years in prison,” instead of “Man works in charity as a new career.” Because we want to know how that transformation happened–not just the fact it happened–and how his life’s conflicts forged a path to the end.

This is also because we, as a society, love rooting for someone, whether that’s ourselves, a sports team, or a character in a book. We like to believe in something, believe in someone, believe anything is possible, believe in hope; and we will follow those efforts until the end. But we can’t root for or believe in something without a journey and conflict.

On top of that, stories have universal themes tied to their central conflict and genre as a lesson for the character to learn. This is what further connects us to the story and characters, while adding more meaning behind what happens.

Yet you can’t have a lesson learned by doing nothing. Learning requires some sort of effort to gain the necessary knowledge (including googling a simple question). Therefore, if a character should grow, learn, and change, they must have conflict on their journey toward their goal. Otherwise, nothing happens. That’s boring.

All in all, this translates to readers and writers enjoying a cycle of telling stories full of meaningful hardships to highlight a theme. From Simba facing the heartfelt journey of learning happiness and retaking Pride Rock from Scar to the gut-punching tragedy of Anakin Skywalker falling to the dark side after failing to embrace morality and change. And yes, tragic endings and negative character arcs count too!

Shaping your story’s central conflict

After all that, how do we make sure we have meaningful conflict, so we aren’t torturing our characters just for the fun of it?

Conflict, and weaving it into your story, from plot outline to scenes, is a topic worthy of its own blog post, if not an entire workshop or course. So I will give an overhead view of how to identify the central conflict in your story, as well as how to tie it with your character.

The central conflict of your story is the primary obstacle your character has to face that defines your plot. This is like Captain America fighting the Red Skull, or Frodo on a quest to destroy the One Ring. Identifying your central conflict answers, “what major obstacle does my character face that creates my novel’s plot?”

List out why your hero cares about that conflict in the first place. Why can’t they walk away from the plot and let someone else handle it? Why is the conflict personal to them? After all, if something didn’t really bother us, then we wouldn’t deal with it, right?

Connect the central conflict with your character’s internal plot (character arc). In fact, both the internal and external plot work together in a story–forcing your character through a journey of change that also showcases your story’s theme as a lesson. Resolving the central conflict is a massive undertaking for your character to experience inside and out, thus making it more important to give them enough reason to stick around.

But they won’t do it willingly. Or, at least, not without proper motivation.

This is where you give central conflict high stakes if it’s not resolved (i.e. the world will end if Frodo doesn’t destroy the ring), and you make it personal to your character. Otherwise, it won’t be worth such an undertaking.

Why? Because people hate change. Most people will choose to settle with current discomforts over something new. Because, no matter how necessary the change may be, it’s easier to keep the status quo.

So, have your central conflict disrupt your character’s status quo at the start of the story, and force high stakes and personal motivation for them to accept the challenge of resolving it.

Let’s use Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz as an example. She finds herself in a new world that’s exciting and different from home–a different she always wanted. So, why go back home? Kansas is full of tornados and a nasty neighbor trying to take her dog.

For starters, her house lands on the Wicked Witch of the East, causing the Wicked Witch of the West to want revenge. Dorothy also finds out that excitement and adventure aren’t all fun and games.

So she accepts the quest to find a way back home. As she travels through Oz, she learns to appreciate her home and family for what they are. Hence “there’s no place like home!”

The central conflict–seeking a way back home–is one for Dorothy to resolve, and only her, because it directly impacts her in several ways. Stakes are raised, for if she doesn’t leave, the Wicked Witch of the West will remain a threat. And since she also dislikes her newfound excitement and adventure, the motivation to return home is more than strong enough. Finally, the story ties it all together with Dorothy learning the lesson to appreciate what she has.

This is what structured and meaningful conflict looks like on a grand scale. As long as your major plot has a personal call to action that your character can’t refuse, and it offers them the opportunity to grow as a person, you’re already taking the right steps.

As a bonus, I added a list of questions at the end if you need an exercise to describe your central conflict and connect it with your story’s internal and external plots.

But there you have it! Conflict is content. Conflict is key.

If we didn’t care about the how, or the journey behind someone’s story, then we wouldn’t have movies, books, or video games. We wouldn’t even have games like Dungeons & Dragons, where we enjoy leveling a character from 1 to 20 and seeing what that process entails. We want to see the character growth, the journey, and how that all concludes–regardless of success or failure, transformation, or tragedy.

This is why conflict matters. And why our poor characters undergo so much of it as “torture” in their journeys.

We love conflict because it makes a good story. So, torture your characters! Make it a hard journey. But remember, make that conflict meaningful so it’s a journey worth experiencing.

Happy writing!

A central conflict exercise

- What major obstacle does your character face that creates your novel’s plot?

- Why does this central conflict matter to your character?

- Does the central conflict force your character a reason to get involved with the plot?

- Does the central conflict raise high personal stakes for your character?

- How will your character’s goal keep them involved in resolving the plot?

- Does the central conflict affect your character’s personal flaw?

- What lesson does your character learn to overcome the central conflict?

- Does the central conflict connect with your character via identity or backstory?

- Does your central conflict allow your character an arc of change or transformation?

- How does your character resolve or fail to resolve the central conflict at the end?