From Ordinary to Extraordinary: How To Write The Hero’s Journey

For writers who plot, the blank page before you start outlining your story is perhaps the most daunting of all. No matter how good the concept is, without a clear idea of where your story will go and a good understanding of beats and pacing, it can feel impossible to get started. A plot template like The Hero’s Journey provides a blueprint around which your story can grow and develop.

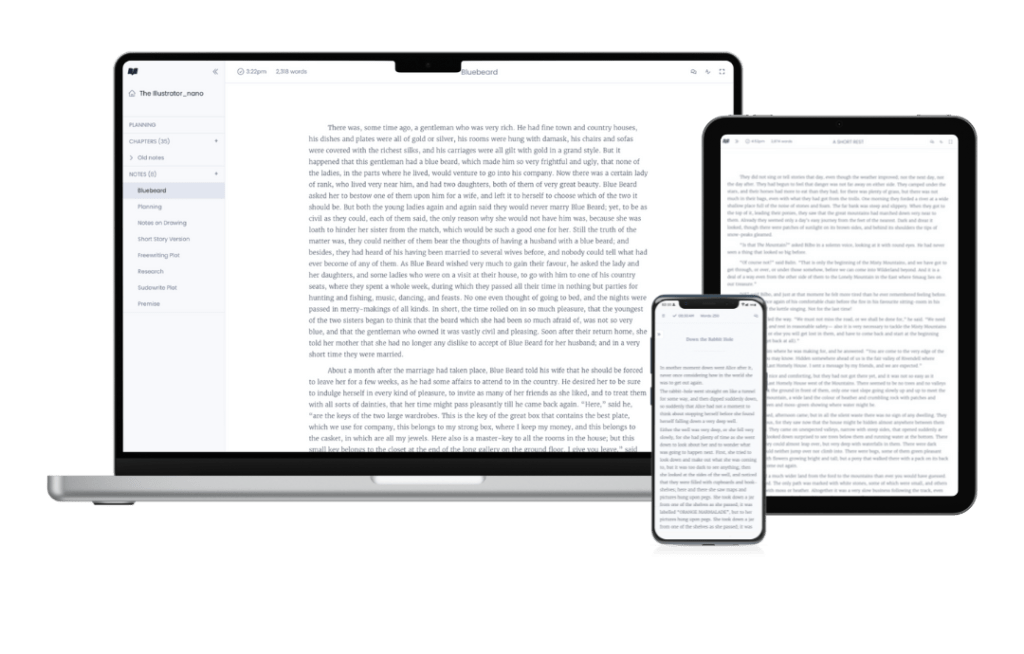

Plotting tools are one of our most requested features. We’d love to build and integrate a solution directly into Novlr, but to help you along your way until that happens, we’ll be looking at some of the most popular story structures and breaking down how to use them to their fullest effect. You’ll be able to access the full repository here as we release them, complete with downloadable templates for you to use in your next Novlr project.

A brief history of the Monomyth

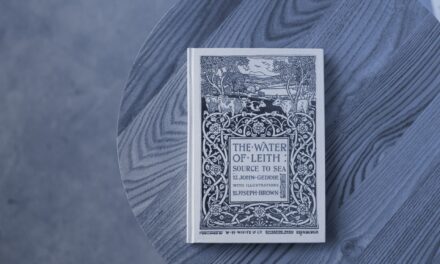

The Hero’s Journey is probably the most well-known of all story structures. Its origins can be traced back to ancient mythology, where heroes embarked on transformative quests, facing trials and triumphs. However, it was Joseph Campbell, the renowned mythologist, who popularised its use and study. In his seminal work, “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” Campbell unveiled the monomyth, a blueprint for heroes’ adventures (what we now call The Hero’s Journey). Divided into three stages—Departure, Initiation, and Return—it takes protagonists on a profound odyssey of self-discovery.

From the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh to the Greek legend of Jason and the Argonauts, countless tales have embraced this structure. More modern examples include The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien, and Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games.

What is The Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is a three-act plot structure that divides into twelve stages with a specific purpose and function within the narrative. The reason The Hero’s Journey is the most popular is that it combines plot direction with character building. It is as much about the characters’ emotional or mental development as it is about the physical journey they undertake.

By travelling a physical path and their inner journey simultaneously, plots based around The Hero’s Journey are full of conflict and tension. Characters struggle and grow, and there is a clear flow to the way the story moves. With an obvious beginning, middle, and end the reader will be on the edge of their seats, but know that they will have a satisfying conclusion by the time they’ve finished your book.

Act 1: Departure

Your hero leaves their ordinary world and takes up the call of adventure. This should make up the first 25% of the story.

Stage 1: The Ordinary World

In the first stage, you should introduce your hero, the world they inhabit, and what their everyday life looks like. This is where your character development will do the bulk of the heavy lifting – your readers need to care about your character before something enters their story to disrupt their existence.

Things to include in Stage 1 are:

- Introduce readers to the Hero in a way that is sympathetic.

- Create a three-dimensional character with wants, needs, desires, and flaws.

- Include a hook that hints at something not quite right in your hero’s life which will ensure they heed the call to adventure. As well as the overarching problem of the narrative, your protagonist also needs a personal problem that must be solved.

- Start building your world – showcase the hero’s idyllic life, but hint at something bigger out in the wider world

Stage 2: The Call of Adventure

Stage 2 should happen around the middle of Act 1, at the 12% mark of your story. It shouldn’t take up too much space and be no longer than a single chapter, two at most. It is in this stage that your hero will have their everyday life disrupted. Whether your protagonist willingly heeds the call of adventure or needs more convincing will determine how much time you spend on this part of your story.

The call of adventure introduces the main conflict. It will come in the form of a challenge or a quest that the hero must embark on before they can return to their idyllic life. Otherwise known as the inciting incident, or hook, it is this call that will determine the trajectory of the rest of your story.

Things to include in stage 2 are:

- An inciting incident. This can come in the form of a quest, the result of your protagonist’s choices, a new discovery, or an accident.

- Show how this incident disrupts your character’s life, and why it is imperative that they are the ones to heed the call of adventure.

Stage 3: Refusal of the Call

If your hero has refused the call of adventure in stage 2, then this is the section where they need to be convinced. If your protagonist is a willing adventurer, then this step can be skipped completely – the importance of stage 3 depends entirely on the nature of the character and the challenge you’ve created.

There are many reasons your hero may initially refuse the call of adventure: modesty, too much risk, age, and beliefs might factor into it. In stage 3 the hero must have no choice but to finally accept the call. This may take multiple attempts with stakes being raised each time, but it must end with the hero finally accepting their task.

Things to include in stage 3 are:

- Your hero’s emotional response to the call of adventure.

- Show what motivates your hero’s refusal, and how that refusal can be overcome. This can be through threats, an increase in the danger the refusal poses to loved ones or even encouragement from family and friends.

- A secondary inciting incident that means the hero can no longer ignore the call.

Stage 4: Meeting the Mentor

Even if your hero willingly heeded the call of adventure, they will still need encouragement and the right tools to succeed on their journey. Stage 4 leads to the end of Act 1 and should bring the story to the 20% mark.

If the protagonist refused the call to adventure in stage 3, then meeting the mentor can serve as the catalyst for an acceptance of their role. If they accepted the call in stage 2, then the mentor can serve as someone who can train the hero in the skills they need to make it home.

The mentor should be an expert, a specialist, or someone whose advice the hero trusts. Whether through training, providing equipment, giving advice, or simply being a ready ear to give the hero the emotional support they need to mentally prepare for what is to come, the mentor will be the one to give the protagonist the final push they need.

Things to include in stage 4 are:

- The hero must gain confidence and feel ready for the journey ahead.

- Clearly show how the mentor helps the hero take up the call of adventure.

- Have a trigger moment where something just clicks for the hero – when they truly know they are ready to take up the call of adventure. This can take the form of an epiphany, mastering a new skill, coming to a personal understanding, or discovering a latent power.

Stage 5: Crossing the First Threshold

Once the mentor has helped the hero accept their role in the call of adventure, and prepared them as best they can, your book should have reached the end of Act 1. This should bring you to the 25% mark of your novel. It represents the first turning point – the moment when your protagonist leaves their ordinary world behind and ventures into the unknown.

By crossing the first threshold, your hero commits to the call of adventure. They should be equipped with the bulk of what they will need to progress on their journey, but don’t be afraid to leave them in the dark about certain things. Whether your hero feels they have learned all they can and are mentally ready to progress, or whether their training is cut short thanks to the actions of your book’s antagonist will yield the same result – your hero is fully dedicated to overcoming the challenge before them.

Stage 5 should include:

- Re-emphasising the task your hero has been called to perform and why it is important.

- Ensure you have fully developed your protagonist and that your readers will be invested in them.

- Show your hero finally leaving their ordinary world behind and what it means to them.

Act 2: Descent and Initiation

The hero enters an unfamiliar world where they encounter new friends and enemies and overcome various trials and challenges. Act 2 should make up 50% of your story (from 25%-75%).

Stage 6: Test, Allies, Enemies

In Act 2, your plot really gets going. From the first moments of stage 6, your hero will face challenges that test their new resolve or abilities. While the mentor has given them a good starting point, your hero still has a lot to learn, and your protagonist will need to learn to rely on the assistance of friends and allies they meet along the way.

Both the hero and the reader should have doubts about their ability to succeed against the overwhelming odds stacked against them. The rules of the outside world are different to where they came from, which makes stage 6 the perfect time for additional character development. The hero and their allies will react to the stresses of challenges in different ways and doubt their abilities or suitability for the task in front of them.

Stage 6 will make up a huge portion of Act 2. It’s when you’ll introduce the majority of your new characters and introduce any additional stakes. You’ll need to develop any allies or enemies and how they react with your hero. Don’t be afraid to play with loyalties – just like your hero, the circumstances of friends and foes can change. Just because your characters are on this journey together, doesn’t mean their motivations are aligned. Each will have had their personal reasons to heed their own call of adventure.

Stage 6 should include:

- Introduce foes and challenges to highlight the danger of this new world.

- Make sure you develop deep and compelling allies and enemies.

- Your hero and their allies should face a series of tests or challenges.

- Don’t be afraid to kill characters off.

- Develop your hero’s character further by showing their doubts and any disagreements they may have with their allies. Show how they work as a group, and whether anyone has any doubts about the righteousness of their quest.

Stage 7: Approach to the Inmost Cave

After the build-up of stage 6, stage 7 is the calm before the storm. After all the world and character building of the trials and challenges that have come before, your hero finally has their goal in sight.

A lot of stage 7 will be about preparation. Your hero and their allies know how to reach their goal, and now they need to rest and gather any necessary supplies, information, or last-minute knowledge. If allies and enemies have come, gone, or switched allegiances in the previous stage, this is the point where the final team is in place. These are the characters who will be with your hero largely until the end.

By the end of stage 7, your hero and their team must be prepared to face what comes next. It’s also a good time to reintroduce the mentor if applicable to provide some much-needed morale boost for the group. Any lingering doubts your protagonist has about their ability to complete their quest must be overcome with a reaffirmation of their commitment to the call of adventure.

Stage 7 should include:

- Moments of character development and growth between your protagonist and their remaining allies.

- Make a plan and gather the necessary supplies and knowledge to ensure success in your hero’s quest.

- Be clear on what your hero’s final goal is and make sure that they are fully prepared for what lies ahead.

- Provide an emotional pause for your characters where they bond as they prepare for their greatest challenge. If your narrative includes a romance, this is where you would have the culmination of this arc.

- Even if your hero still has doubts, make sure that they will not inhibit their performance or readiness for the final stage of their quest.

Stage 8: The Ordeal

This marks a mini climax of your novel as the rising action of your narrative begins to peak. Your hero will face a series of challenges as they and their allies work toward their goal and face the antagonist. Stage 8 is the culmination of your story’s central conflict. It brings together everything your hero has learned not only from their mentor but also through the trials and challenges of stage 6 to emerge victoriously.

It is at this point that your hero will undergo a transformation. There must be a metaphorical death and rebirth (although for some narratives this can be literal), where they leave behind who they were in stage 1 and become a stronger, more powerful version of themselves. This death can come in the form of a significant sacrifice, or the death of a character who is close to them – whatever this catalyst is, it must be powerful enough to change your hero as a person.

Depending on the nature of your story, where the ordeal happens and whether it is successful may vary. A successful ordeal will likely happen late in Act 2 as a natural climax. If the hero is unsuccessful, however, then the ordeal should happen closer to the middle of Act 2 as it will introduce more stakes and tension that will need to be explored and developed.

Stage 8 should include:

- A dark moment for the hero like the death of a mentor or ally, their own death, a stunning revelation, or a painful sacrifice.

- Strong character building highlighting the changes the hero must go through to become the best and most powerful version of themselves.

- A moment of confrontation, whether it be facing a serious challenge or encountering the antagonist.

- Show how the hero’s world has changed by what they have endured.

Stage 9: Reward (Seizing the Sword)

Whether a success or failure, your hero will have passed through the ordeal, receiving their reward, marking the end of Act 2. This reward can be knowledge or an object – whatever form it takes, it will be the catalyst that propels them toward the final battle and ensures their survival. No matter the losses of stage 8, this is a moment of celebration for your hero and gives your readers a breather before your story ramps into the climax.

While this moment represents a victory for your protagonist, it’s also a good time for your characters to remember those they have lost along the way. It’s an emotional reset where your hero and their allies can come to terms with everything they have endured, and what is yet to come.

Stage 9 should include:

- The acquisition of the reward, and a clear indication of how it will help the hero achieve their ultimate goal.

- A reflection on what your hero has learned, and how they have changed.

Act 3: Return

Your hero enters the final battle and begins their journey home but is a very different person from when they left their ordinary world. It makes up the final 25% of your story.

Stage 10: The Road Back

With the reward now firmly in their possession, the hero begins their journey home. Instead of being a simple journey, however, this is where you will increase the tension and heighten the stakes of your narrative, leading to the ultimate climax of your story. It is in stage 10 that your protagonist must face the consequences of the outcome of stage 8: the ordeal.

This part of the narrative will mark the catalyst that leads to the climax. It is where your hero will complete their quest, leading them to the final battle. The stakes should be higher than when your hero undertook the ordeal – with the mission not yet fully complete, there must be severe consequences if they were not to complete their quest.

Stage 10 should include:

- A sense of urgency. Make clear what it would mean for your hero and their world if they don’t succeed in the final confrontation.

- Highlight the consequences of the ordeal and the reward and how it will lead to the final confrontation.

- Show how your hero has changed and highlight their newfound confidence post-ordeal.

Stage 11: Resurrection

This is where your story finally reaches its climax. The stakes should be higher and the difficulty more acute than anything your hero has faced before. It should tie together all the lessons your hero has learned during their journey.

This climax carries all the emotional weight of the rising action – your hero is fighting for a cause and for those they have lost along the way. After this battle they will have fully embraced the role of hero and can return to their ordinary world, changed by their experience.

Stage 11 should include:

- The final battle, showing how the hero has grown and developed over the course of the story to emerge victorious.

- Show how the reward makes the hero’s victory possible.

- Dramatise the hero’s sacrifice. This sacrifice can be metaphorical or literal. It could be a physical sacrifice or the sacrifice of who they were before.

- Prepare the hero for a triumphant return to their ordinary world (even if only in memory).

Stage 12: Return with the Elixir

Having undergone profound change, your hero is now ready to return home. The return should make up only 5% of your narrative, and reaffirm your protagonist’s growth and development. Have your hero reflect on their experiences, what they’ve learned, and the people they have met and lost along the way.

Your hero can now look forward to a new phase of life, whether that be settling back into their ordinary world, or seeking out a new adventure, finding their old life incompatible with their growth. Either way, on their return, the hero is rewarded and celebrated. They have faced danger and challenges, and have come through it, which earns them the respect of those they have left behind, or at least a new perspective for both the hero and the people of the ordinary world to consider.

Stage 12 should include:

- A triumphant return highlighting how the ordinary world seems different to the hero now.

- Reaffirm your hero’s growth, and show whether they decide to settle into a calm life in the ordinary world, or if they have developed beyond what the ordinary world can offer them and choose to embark on further adventures.

- Make clear how your hero’s ordinary world was changed by their journey, and how the events of stage 11 make a difference to the people of that world.

Download the template

You can download the template below to use it for your next project and import it directly into Novlr. If you go to your Projects page from your Novlr dashboard and click on “Import,” the template will automatically split your project into acts and sections for easy plotting!

There is no “right” way to outline a novel. That’s why there are lots of different story structures out there. The trick is finding one that works for you, and adapting it to suit your needs. Once you understand the way story structure works, it’s easy to bend the rules to make something completely unique to you.

What a good plot template can do is provide a springboard for your ideas, giving them fertile soil in which your imagination can help them flourish into the novel they deserve to be.

Hi: I like what I read here and will revisit as I approach the start of coming to grips with my next novel. Right now I’m editing my work in progress and figure life might be easier on my brain if I followi along the pathway you have outlined here. Thanks

So glad it’s proving useful. Having a template for story beats when you’re editing is an absolute life saver. I’ve found with my own work, even if I haven’t written with a defined plot structure from the outset, the content is usually there and I might just have to move things around for the sake of pacing.

If there’s a particular plot structure or a specific genre you’d like to see, feel free to let me know!